Heartburn (1986): "Ew, men"

In part 2 of our Heartburn 40th anniversary celebration, we watch the film adaptation of Nora's novel so that you don't have to.

Note: This newsletter will cut off if read in your email. Click the title to read it on Substack for the full experience.

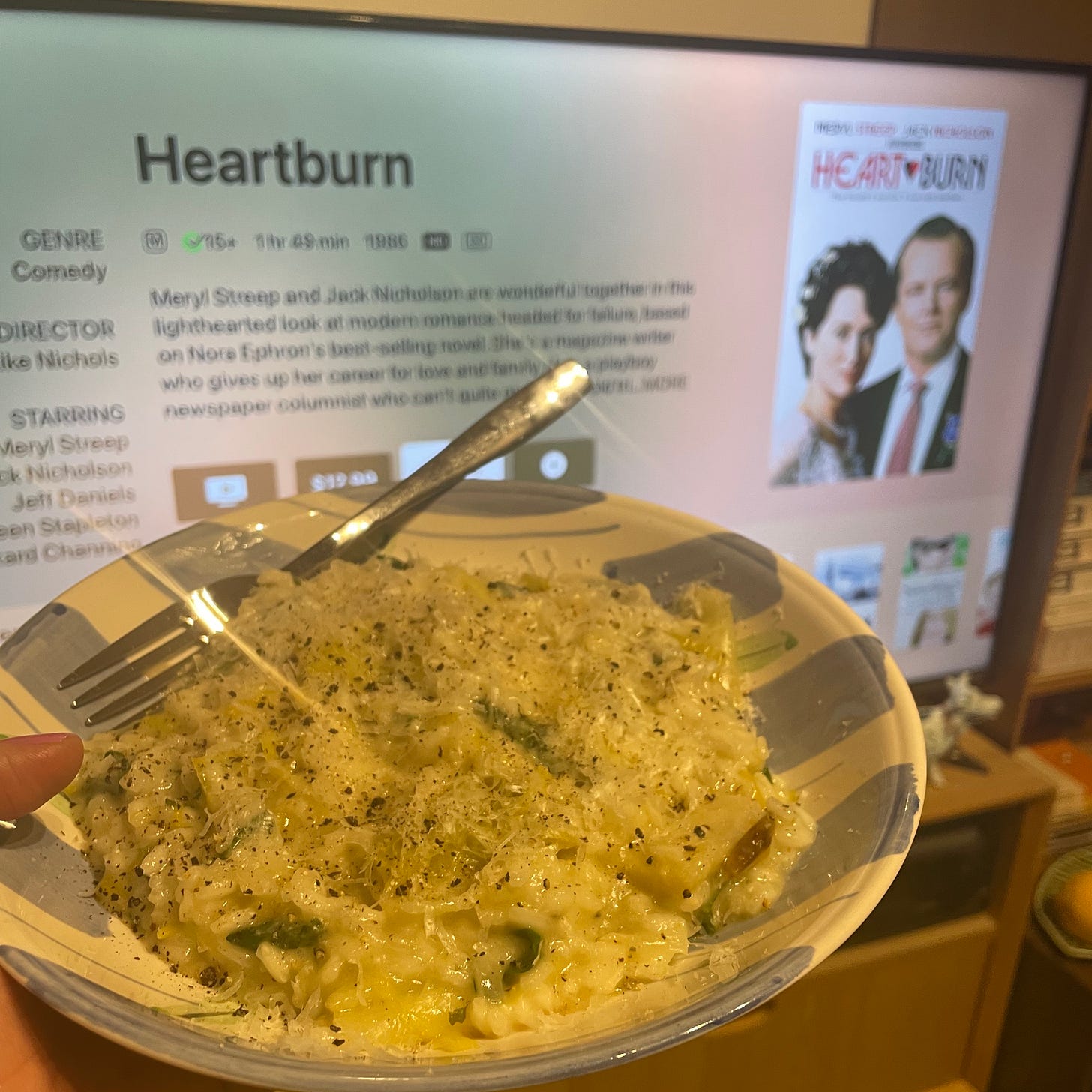

This month we watched Heartburn, the film adaptation of Nora’s novel of the same name, with a script written by Nora herself.

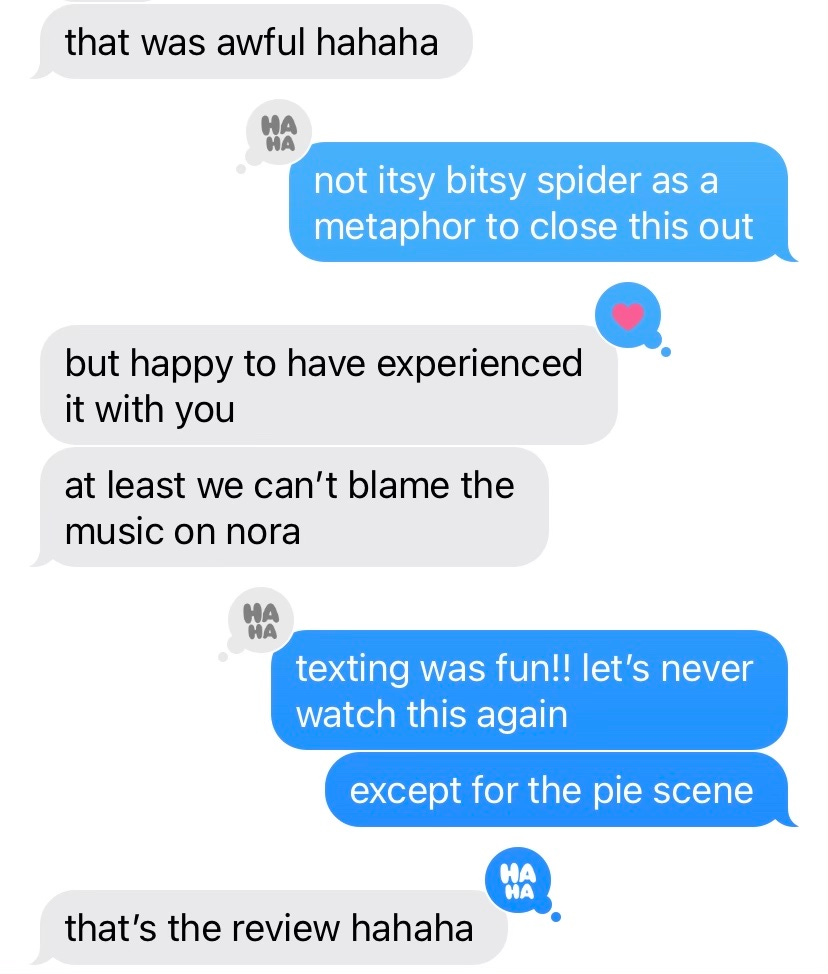

We can’t in good faith recommend that you do the same. But if you must, at least watch it at the same time as your best friend so that you can help each other through the experience.

40 Years of Heartburn

Marama: We aren’t the only ones consumed by Heartburn at the moment. Critics revisited the novel in honour of its 40th anniversary, all vying for a different angle and those much desired clicks (in extremely classic fashion, the one Australian outlet to cover Heartburn published a month later than everyone else). There were fairly traditional book reviews in NPR, Vox, and the Washington Post. Eater tackled Heartburn as a food memoir, while The Atlantic grappled with the different ways of reading the novel, picking up on the tension we raised in our own review.

The Independent opted to put Heartburn in conversation with subsequent generations of (white) women comedians, such as Amy Poehler and Phoebe Waller-Bridge, writing “Heartburn turned Nora Ephron into the poster girl for millennial writers.” They also took the opportunity to interview journalist Ilana Kaplan, who is writing a book about Nora.

Jezebel also took the interview route, opting to speak with Nora’s sister Delia about Heartburn’s legacy. Of the Nora vs Rachel question, Delia said:

“Rachel absolutely is Nora. It isn’t all of Nora, but everything Nora thought about at that time of her life is in this book. But that is why it’s so universal: When things are that personal, that’s when they become universal.”

Finally, Time (inexplicably) used the anniversary as an opportunity to mount a spirited defence of the Heartburn movie, calling it “her best film."1 To that, I can only say: trying to write a unique hot take to peg to the SEO for an upcoming anniversary is not an enviable task, and also, that writer is out of their damn mind.

Contemporary reviews

Once again, Hollie dived into the historical archive to see what reviewers at the time thought of Heartburn as a film.

America

Hollie: U.S. reviews of Heartburn published in 1986 and 1987 can be sorted into four main categories: raves, ‘it’s not that bad!’, ‘it is that bad!’ and ‘what does Carl think about all this, anyway?’

Rave reviews are hard to track down, but they do exist: Paul Attanasio in the Washington Post declared the film was a “masterpiece, a collaboration of mature artists at the peak of their craft,” “seriously funny,” and a showcase of Nichols’ directorial prowess.2 Admittedly, Attanasio felt the need to pen a defence of his review mere weeks later, after most critics “greeted ‘Heartburn’ with disappointment or … downright hostility.” After conceding that maybe he was “wrong in calling ‘Heartburn a masterpiece,’ Attanasio doubled down, arguing that it was a “classic film” doomed to be “misunderstood in [its] own time.”3 The defence of his original review is longer than the review itself, which I think is very funny!

In the ‘it’s not that bad!’ crowd, Johanna Steinmetz concedes that the film “lacks a certain bite,” but has nice things to say about Streep, Nicholson, and the “stellar supporting cast,” and thinks it has an “excellent sense of place.” She concludes that the “punches have been pulled,” but that “there is plenty in this movie to keep one entertained.”4

Then we have the critics who vehemently disagreed with Attanasio. Roger Ebert: “[t]his is a bitter, sour movie about two people who are only marginally interesting.”5 Charles Champlin: “It’s hard to imagine that the year will provide a more disappointing film than ‘Heartburn.’”6 Sheila Benson: “‘Heartburn’ is thin stuff from rich talents.”7 Rita Kempley: “‘Heartburn’ has been so waspified you’d think Nora Ephron had married Woodward instead of Bernstein.”8

Finally, the category of review I wasn’t expecting—but probably should have!—the ones that centre (poor old) Carl. Playboy published an interview with Carl in September 1986, and some reviewers centred these comments in their pieces.9 William C. Trott, for United Press International, writes about Carl’s perspective on Heartburn: “‘It’s got a nasty tone, a smarmy edge’,” Bernstein says of the book in a Playboy interview ‘...it is prurient. It obliterates everybody’s dignity.’”10

The UK & Australia

After reading more UK reviews, I have to ask: British people, are you okay? More than one reviewer described the marriage between Rachel and Mark (pre-cheating) as “idyllic,” which I think anyone who has sat through Heartburn can agree is wildly concerning.11

At least the Brits can be relied upon to have the funniest—as well as the most concerning—Takes. I was particularly mesmerised by E. Graydon Carter, who, in the Independent Weekender, wrote an extended defence of poor old Carl. Carter shares some interesting details about Carl’s legal power to demand changes to the script, and he also refers to Nora as “Mrs. Bernstein.” Okay!

This headline immediately makes me think about public hand wringing about Taylor Swift writing songs about her exes in the 2010s. And look, while there is an interesting conversation to have about power dynamics in a relationship when one person is a (famous) writer and the other is not, I’m not sure that it quite applies when the ‘not-writer’ in question is the journalist who broke the Watergate scandal.

Finally: not too much to report from Australia. Filmnews labelled the film a “happily heterosexual feminine revenge fantasy” and yet somehow also a “stretched-out sitcom.”12 And everyone else seemed more interested in Streep and Nicholson than Ephron and Bernstein.13

Our reviews

Hollie: “If your husband is cheating on you,” Nora Ephron quipped in 2004, “get Meryl to play you. You will feel much better.” The crowd, assembled to see Streep receive her AFI Life Achievement Award, laughed at Nora’s self-effacing reference to Heartburn. They continued to laugh at Nora’s jokes (including some that have dated…poorly), and Streep herself seemed particularly tickled by one of Nora’s final, bold claims: “[Meryl] plays us all better than we can play ourselves.”

Here are some of my thoughts while watching the clip from this event:

Nora Ephron looking very chic;

Nooooo, not a Lindy Chamberlain joke;14

It’s very interesting to see Ephron publicly claim Rachel Samstat as a version of herself;

Noooo, not a racist joke;

We’re so lucky to have Meryl Streep;

That’s wrong: Meryl couldn’t play Nora better than Nora could play herself.

The central failure of Heartburn (1986) is that Rachel Samstat never quite feels like a fully-formed person. In the book, Rachel-as-Nora is complicated, funny, self-reflective, occasionally pathetic, and passionate about her work, family, and friends. In the film, Meryl-as-Rachel is (inexplicably) in lust and in love with Jack Nicholson’s Mark Forman, transcendentally happy to be a mother, and then heartbroken. But without the deep interiority of the book, we don’t get many chances to see the wry humour, wit and ambition that defines Rachel in the book.

Take Rachel’s passion for food and cooking. In the film, we see Rachel present food to people: the spaghetti that kicks off the ill-fated relationship, the chicken that Mark chows down preemptively, the dinner-party lamb abandoned as Rachel goes into labour, and, of course, the key lime pie. But although the food is physically present, you don’t really feel its emotional resonance. Why is cooking so important for Rachel? What does it mean? What does she think and feel about her career, and putting her career on hold? The recipes and reflections on food that cut through the novel tell us a lot about Rachel, and how she views the world, and how she feels about things. Their absence is sorely missed.

Now, I’m sure some of the blame for Heartburn’s uneven script can be placed at Carl Bernstein’s feet. As part of the couple’s divorce proceedings, he secured the right to review the film’s script, and as (presumably) his biggest fan E. Graydon Carter noted, there “was clause upon clause as to how Bernstein and the two boys would be portrayed in the movie.” In 1985, “Bernstein filed a contempt motion to force Ephron to implement changes he had asked for.” When he viewed the film’s final cut in January 1986, Carl reportedly said:

"[T]he movie comes closer to the truth than the book, both in terms of telling and what actually happened. Whether that had anything to do with what actions I took, well, I do like to think that had something to do with it.”15

Hmmmm.

I think the fact that the side characters, particularly the friends, fizzle with interest and energy, lends some credence to the notion that Carl substantially interfered with the characterisation of Rachel and Mark. I thoroughly enjoyed Catherine O’Hara as a gossipy Texan, I thought the group therapy scenes were genuinely very, very funny, and I wanted approximately 50% more Stockard Channing. In these sections we can see glimmers of what would make Nora’s future scripts—or, at least the script for the one Nora film I have seen and absolutely loved (When Harry Met Sally)—so charming and compelling. Bring on the depictions of friendships, please!

Marama: What else is there to say about this Heartburn adaptation? It’s just not very good. My viewing experience peaked when my partner asked, over the opening credits, “Is Stockard Channing Channing Tatum’s father?” and went downhill from there.16

For me, this film is a failure of adaptation. Despite the combination of Nora as screenwriter, Meryl as star, and Mike Nichols as director which had proved so winning for Silkwood only three years prior, the film is a boring chronicle of a relationship break down between two fairly tedious and one-note characters.17

The first big loss in the change in medium is Rachel’s internal monologue, which is either removed entirely or translated into awkward dialogue. Without her narration, we lose the dynamism, the humour, and even the uncomfortable self-pity which made her so interesting in the novel. Arguably, this narration was so fundamental to the novel’s success that it makes any adaptation into a visual medium simply impossible.

But Nora hasn’t done herself any favours with her other adaptation choices. Most notably, she has chosen to set the film chronologically, rather than opening with Rachel’s response to Mark’s affair, as the novel begins:

“The first day I did not think it was funny. I didn’t think it was funny the third say either, but I managed to make a little joke about it.”

Instead, the film opens with Rachel and Mark meeting at a friend’s wedding. From there we watch their romance quickly build and then just as rapidly fall apart through a collection of scenes rather than any targeted narrative. The film demands that we see the passion between this couple, without giving us any reason to believe it. When Mark cheats, it is inevitable, rather than heartbreaking. You spend most of the film wondering why these two people would ever enter a relationship in the first place, let alone stay together long enough to have two children.18

Part of the reason the relationship didn’t land for me was the uncomfortable thought I had throughout the film, that Meryl simply….isn’t very good in this. Jack Nicholson is his usual unpleasant self, coming off here as a truly repugnant man and awful father, and I spent far too much time googling some version of “Jack Nicholson sex symbol???” (with little luck) to try and understand how he may have been viewed in the 1980s.19 But Meryl is also flat and obvious. She had already won two Oscars (and been nominated for an additional four) by the time of filming Heartburn, so I wonder how much of her performance was instead a reflection of the limitations of script—or perhaps a response to being relentlessly hit on by her aforementioned slimy costar.20

There are a few classic Nora moments which do manage to shine through. Every scene where we step away from Rachel and Mark to focus on their friends is a highlight. Stockard Channing and Richard Masur have shades of Carrie Fisher and Bruno Kirby in When Harry Met Sally, and the scenes with Rachel’s therapy group (where Mark is notably absent) are genuinely extremely funny, and allow Meryl to showcase what she can really do.

My overall impression was that by the time she wrote the script for Heartburn, Nora was over it. Over this book, over writing about her relationship with Carl, and over negotiating with him over the film. I sincerely hope she got paid extremely well for the script. And I wonder if she had already turned her mind to new and exciting projects, like a script she had starting working on in 1986, about two friends named Harry and Sally…

Up next: When Harry Met Sally… (1989)

In 1986, the year that the Heartburn film was released, Nora wrote the script for another film about a somewhat unlikely couple who would be translated through the eyes of a male director.

That’s reason enough for us to turn to the first of her classic romantic comedies in May. Plus, we all need a lift after slogging through Heartburn. We hope you’ll join us!

It’s worth noting that all of the elements praised—its honesty, its depiction of the slow car crash of this relationship, and its protagonist—are all lifted directly from the novel, where they were implemented with much greater success.

Paul Attanasio, “Movies,” Washington Post, July 25 1986. See also: Richard Corliss, “Cinema: Love's Something You Fall in Heartburn,” Time, August 4 1986.

Johanna Steinmetz, “Heartburn’ Loses Some of Its Acid In the Screen Version,” Chicago Tribune, July 25 1986.

Charles Champlin, “‘Heartburn’: It Hurts More Than You Think,” Los Angeles Times, July 29 1986.

Sheila Benson, “Movie Review: ‘Heartburn’s Slick Souffle,” Los Angeles Times, July 25 1986.

Rita Kempley, “‘Heartburn’: Hamstrung,” Washington Post, July 25 1986.

I can’t believe I genuinely had to look up an edition of Playboy for the article(s)—only to discover Playboy is extremely well hidden behind a paywall! I simply will not pay to view the article. See here if you’ve got $8 for a one month membership!

William C. Trott, “Bernstein Has a Bad Case of Heartburn,” United Press International, July 23 1986.

“Your Way,” Daily Mirror, 30 January 1987, 19; Kim Adams, “Striking a chord,” Fulham Chronicle, 8 January 1987.

“Actress faces daily tug: Every film the last for Streep,” Canberra Times, 20 March 1986, 2; “Plot is not likely to attract those seeking escapism,” Canberra Times, 19 October 1987, 26; “Heartburn of modern marriage portrayed,” Canberra Times, 19 February 1987, 5. Best unrelated headlines turned up by the search term ‘heartburn’ in 1986: “Psst…do you want to work as a spook?” and “the versatility of baking soda.”

Lindy Chamberlain was pilloried in the press after her daughter Azaria was killed by dingoes near Uluru in Australia. Chamberlain was initially found guilty, and was the butt of countless jokes, including this one from Ephron. I’d recommend this podcast by Australian historians to learn more about this heartbreaking story.

E. Graydon Carter, “Bernstein,” Independent Weekender, October 4 1986, 9.

Incredibly, this question is the basis for a number of clickbait articles, including this quiz: “Stockard Channing Or Channing Tatum: Can You Tell The Difference?” I got 8 out of 10.

Silkwood was nominated for five Oscars, including Best Director for Nichols, Best Actress for Streep, and Best Screenplay for Nora and her co-writer Alice Arlen.

In Nora’s defence, this may genuinely be how she felt by the time of writing the script. But while an honest reflection, good cinema it is not.

Ironically, Nora and Carl’s divorce settlement stated that “the father in the movie 'Heartburn' will be portrayed at all times as a caring, loving and conscientious father.” I don’t know what film Carl signed off on, but if this was his idea of a caring father……yikes.

Quelle surprise: “Meryl Streep Had to Fend Off Jack Nicholson Repeatedly While Filming Heartburn”. Adding more complications to the film’s production history, in his biography of Nichols Mark Harris reported that the director had a drug-fuelled breakdown between the end of Heartburn filming and its release. Nicholson himself was a late replacement, after Nichols fired Mandy Patinkin after one day of filming.